The Communist Party of India (Maoist), commonly known as CPI (Maoist), represents one of the most persistent and complex insurgencies in contemporary India. This Marxist-Leninist-Maoist organization has been at the center of what former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh once described as the country’s “biggest internal security challenge.” As India approaches the government’s self-imposed deadline of March 2026 to completely eradicate Maoist influence, understanding this organization’s history, ideology, structure, and impact becomes crucial for comprehending modern India’s security landscape.

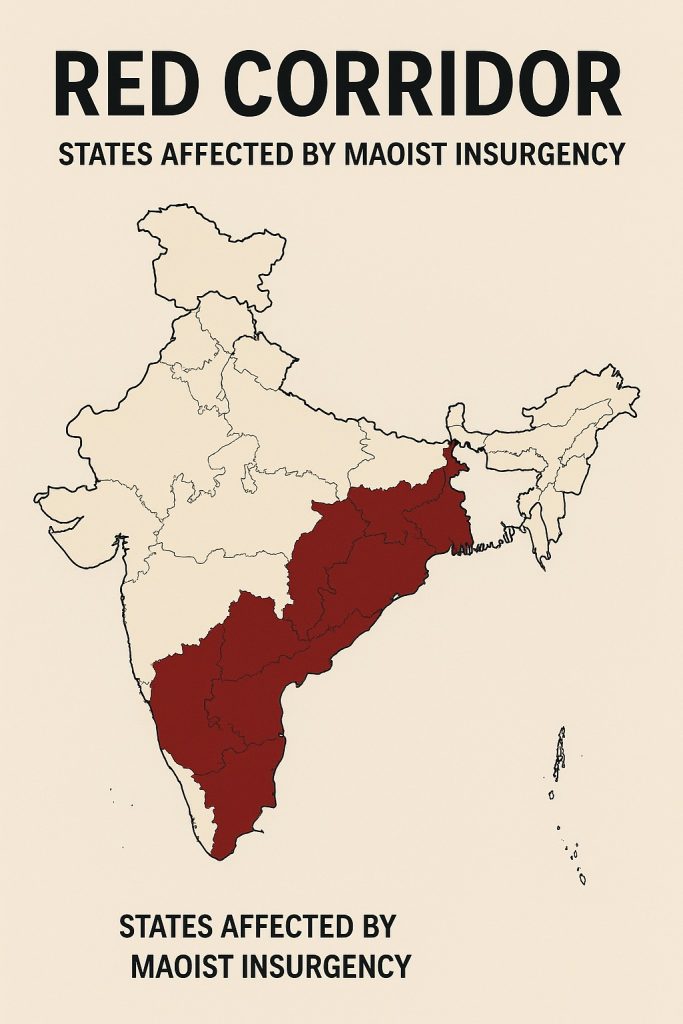

Map showing India’s Red Corridor which highlights states affected by Maoist insurgency in dark red worldview.stratfor

The CPI (Maoist) emerged from decades of revolutionary movements rooted in agrarian discontent and class struggle. Since its formation in 2004 through the merger of two major Maoist groups, the organization has challenged the Indian state across vast swathes of the country, particularly in the mineral-rich tribal belt known as the “Red Corridor.” Despite significant government counter-insurgency efforts, the movement continues to operate across multiple states, adapting its strategies while maintaining its core objective of overthrowing the existing democratic structure through armed revolution.

Historical Genesis and Evolution

Roots in Peasant Uprisings

The ideological foundations of CPI (Maoist) can be traced back to the Telangana Uprising (1946-1951), an armed peasant rebellion led by the Communist Party of India against feudal landlords and the princely state of Hyderabad. This uprising, along with the Tebhaga movement in Bengal (1946), established the precedent for communist-led agrarian struggles in India. However, both movements were eventually terminated following decisions by communist leadership in the USSR and India.

The modern Maoist movement in India gained momentum with the 1967 Naxalbari uprising in West Bengal. On May 25, 1967, an armed peasant uprising led by Kanu Sanyal of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) erupted in Naxalbari village in Siliguri district. This 72-day rebellion, though crushed by police action, sparked a revolutionary movement that would eventually evolve into today’s Maoist insurgency.

Formation of CPI (Marxist-Leninist) and Subsequent Splits

The Naxalbari movement led to the formation of the All India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries (AICCCR) in 1967, which later became the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) or CPI (ML) on April 22, 1969, under the leadership of Charu Mazumdar. The party adopted a strategy of armed struggle, rejecting parliamentary democracy in favor of revolutionary violence.

However, the movement faced severe repression during the early 1970s. Operation Steeplechase, conducted jointly by the army and police from July 1 to August 15, 1971, resulted in the arrest of approximately 8,400 Naxalites, including top leadership. The death of Charu Mazumdar in police custody on July 28, 1972, led to the collapse of central authority and the fragmentation of the movement into numerous factions.

The Path to Unification

The 1980s witnessed the emergence of two major Maoist groups: the People’s War Group (PWG) formed by Kondapalli Seetharamaiah in 1980, and the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC), which evolved from the earlier Dakshin Desh group. These organizations operated independently across different regions, with PWG primarily active in Andhra Pradesh and MCC concentrated in Bihar and Jharkhand.

The 1990s marked a significant phase of reunification efforts. In September 1993, the MCC, PWG, and CPI (ML) Party Unity formed the All India People’s Resistance Forum (AIPRF) to coordinate their activities. This collaboration eventually culminated in the historic merger of September 21, 2004, when the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) People’s War and the Maoist Communist Centre of India united to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist).

Organizational Structure and Leadership

Hierarchical Command Structure

The CPI (Maoist) operates through a sophisticated hierarchical structure designed to maintain discipline while ensuring operational flexibility. At the apex sits the Party Congress, convened every five years, which serves as the highest decision-making body. Between congresses, the Central Committee (CC) consisting of 37 members functions as the supreme authority, with a 14-member Politburo (PB) handling day-to-day affairs.

The organizational hierarchy descends through Special Area Committees, State Committees, Regional Committees, Zonal Committees, Area Committees, and finally to the basic unit—the Party Cell comprising three to five members. This structure ensures both centralized ideological control and decentralized operational capability across diverse geographical regions.

Central Military Commission and Armed Wing

A crucial component of the CPI (Maoist) structure is the Central Military Commission (CMC), responsible for military strategy and the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA). The CMC oversees several specialized departments including the Technical Research and Arms Manufacturing Unit (TRAM), Regional Commands, Special Action Teams, Military Intelligence, and the Tactical Counter Offensive Campaign.

The PLGA, formed on December 2, 2000, represents the military arm of the organization with an estimated strength of 9,000-12,000 cadres. It operates through a three-tier structure: Main Force (companies and platoons), Secondary Force (guerrilla squads), and Base Force (people’s militia and self-defense squads). In regions like Bastar, the people’s militia alone is estimated to number 30,000 personnel.

Leadership Evolution and Current Status

Muppala Lakshmana Rao, alias Ganapathy, served as the General Secretary from 1992 until 2018, when he stepped down due to ill health and advancing age. His successor, Nambala Keshav Rao (alias Basavaraju), led the organization until his death in a security forces encounter on May 21, 2025. The current leadership structure remains largely secretive, though intelligence sources suggest that senior commanders from Andhra Pradesh or Telangana are likely to assume key positions.

Ideological Framework and Strategic Vision

Marxism-Leninism-Maoism as Guiding Ideology

The CPI (Maoist) adheres to Marxism-Leninism-Maoism (MLM) as its ideological foundation, viewing it as the highest stage of communist thought. The organization’s theoretical framework is based on Mao’s Theory of Contradiction, which identifies four fundamental contradictions in Indian society: imperialism versus the Indian people, feudalism versus the broad masses, capital versus labor, and internal contradictions among ruling classes.

According to CPI (Maoist) analysis, the contradiction between feudalism and the broad masses represents the principal contradiction requiring resolution through New Democratic Revolution (NDR). This theoretical framework justifies their strategy of armed struggle as the only viable path to social transformation.

Strategic Objectives and Long-term Vision

The organization’s strategic vision encompasses both immediate and long-term objectives. Their Party Programme outlines several key goals: declaring India’s 1947 independence as “fake,” establishing political power through armed struggle, following the Chinese model of encircling cities from countryside, uniting with South Asian Maoist forces, supporting nationality struggles, and ultimately establishing a “People’s Democratic Federal Republic of India”.

The CPI (Maoist) envisions their struggle progressing through three strategic stages: Strategic Defensive (current phase), Strategic Stalemate, and Strategic Offensive. In the current defensive phase, their immediate objectives include transforming guerrilla zones into liberated base areas and converting the PLGA into a full-fledged People’s Liberation Army.

Compact Revolutionary Zone Concept

A central element of Maoist strategy involves creating a Compact Revolutionary Zone (CRZ) or “Red Corridor” extending from Pashupati (Nepal) to Tirupati (Andhra Pradesh). This ambitious plan aims to establish contiguous liberated territories across the mineral-rich tribal belt of central and eastern India, providing a secure base for expanding revolutionary activities nationwide.

Current Operational Status and Geographical Presence

The Shrinking Red Corridor

The geographical extent of Maoist influence has undergone dramatic reduction in recent years due to sustained government counter-insurgency efforts. From a peak of 182 affected districts across 20 states in 2013, the number has steadily declined to just 38 districts in 2024, with projections indicating further reduction to 18 districts by 2025.

Decline in Left Wing Extremism (LWE) affected districts in India from 2013 to 2025, showing the government’s successful counter-insurgency efforts against CPI (Maoist)

Currently, the CPI (Maoist) maintains significant presence in only six “most affected” districts: four in Chhattisgarh (Bijapur, Kanker, Narayanpur, and Sukma), one in Jharkhand (West Singhbhum), and one in Maharashtra (Gadchiroli). Additionally, six “districts of concern” require continued vigilance, spread across Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and Telangana.

Operational Capabilities and Tactics

Despite territorial losses, the CPI (Maoist) continues to demonstrate sophisticated operational capabilities. The organization employs asymmetric warfare tactics including guerrilla attacks, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), abductions of government officials, and targeted assassinations of perceived “class enemies”. Their strategy emphasizes mobility, local support, and exploitation of difficult terrain to evade security forces.

The Maoists have developed expertise in manufacturing explosives using ammonium nitrate, often acquired through pilferage from mining operations. Intelligence reports indicate they have stockpiled significant quantities of weapons and explosive devices, including an estimated 6,000 rocket launchers. Their technical capabilities are enhanced by the Technical Research and Arms Manufacturing Unit, which focuses on indigenous weapons development.

Government Response and Counter-Insurgency Strategy

Evolution of Counter-Insurgency Approach

The Indian government’s response to the Maoist challenge has evolved from purely security-focused operations to a comprehensive strategy combining development initiatives with targeted military action. Initially, operations like the controversial Salwa Judum in Chhattisgarh (2005-2011) relied heavily on civilian militia, but these were disbanded by Supreme Court order due to human rights violations.

The current approach, formalized under Operation SAMADHAN (launched in 2017), emphasizes a multi-pronged strategy encompassing security, development, infrastructure, public perception management, and coordination between various agencies. The government has set an ambitious target of completely eliminating Maoist influence by March 31, 2026.

Recent Operational Successes

Government forces have achieved significant tactical successes in recent years. In 2024 alone, 219 Maoist cadres were eliminated compared to just 22 in 2023 and 30 in 2022, marking a sharp escalation in counter-insurgency effectiveness. By March 2025, security forces had killed 90 Maoists, arrested 104, and facilitated the surrender of 164 others.

The establishment of 280 new security camps since 2019, creation of 15 Joint Task Forces, and deployment of six additional CRPF battalions has significantly enhanced the government’s operational capacity. These measures have been complemented by National Investigation Agency actions targeting Maoist financing networks and logistics support systems.

Development and Infrastructure Initiatives

Recognizing that security operations alone cannot address the root causes of insurgency, the government has substantially increased development spending in affected areas. Under the Special Central Assistance scheme, the most affected districts receive ₹30 crore annually while districts of concern receive ₹10 crore for infrastructure development.

The “Dharti Aaba Janjatiya Gram Utkarsh Abhiyan” launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in October 2024 represents a comprehensive rural development initiative targeting over 15,000 villages and benefiting nearly 1.5 crore people in LWE-affected areas. The program focuses on improving connectivity (roads, mobile networks, and financial services) to integrate remote tribal areas into the mainstream economy.

Human Rights Concerns and Civil Society Impact

Violations by Both Sides

The Maoist conflict has resulted in serious human rights violations by both insurgents and security forces, with civilian populations bearing the brunt of violence. According to government data, since 2001, Maoists have killed 5,811 civilians and 2,081 security personnel, with the overwhelming majority of civilian casualties being tribals whose cause the Maoists claim to champion.

Maoist abuses include targeted killings, public executions through “people’s courts,” forced recruitment of children, sexual exploitation of women cadres, and coerced abortions. The organization’s system of “levies” (extortion) and violent punishment of suspected informers has created a climate of fear in affected areas.

Security forces have also committed significant violations, including arbitrary arrests, torture, extrajudicial killings, and collective punishment of villages suspected of Maoist sympathies. The now-disbanded Salwa Judum and Special Police Officers (SPOs) were particularly criticized for human rights abuses, leading to their prohibition by the Supreme Court in 2011.

Impact on Civil Society and Development

Civil society activists working in Maoist-affected areas face threats from both sides, with Maoists labeling them as police informers while security forces demand intelligence cooperation. This environment has severely constrained humanitarian work and development activities in affected regions.

The insurgency has significantly hindered economic development in mineral-rich tribal areas, with Maoists targeting infrastructure projects, schools, and health centers as symbols of state authority. The disruption of governance structures and intimidation of local officials has created a vacuum that Maoists exploit to establish parallel administrative systems.

International Context and Global Maoist Networks

South Asian Connections

The CPI (Maoist) has consistently pursued regional connections with other Maoist groups across South Asia. The organization’s program explicitly calls for uniting with Maoist forces in the region to overthrow the Indian state. While concrete evidence of substantial material support remains limited, ideological exchanges and coordination with groups in Nepal and other countries have been documented.

The organization’s vision of revolution extends beyond national boundaries, viewing their struggle as part of a broader international communist movement. This perspective influences their strategic thinking and provides ideological justification for their activities within a global revolutionary framework.

Learning from Global Insurgencies

CPI (Maoist) strategy demonstrates adaptation of successful insurgency models from other countries, particularly drawing from Chinese communist revolution experiences and Vietnamese anti-colonial struggles. Their emphasis on protracted people’s war, base area development, and gradual territorial expansion reflects classical Maoist strategic thinking adapted to Indian conditions.

The organization has also studied more recent insurgencies, incorporating modern communication technologies, sophisticated explosive devices, and urban networks into their traditional rural guerrilla warfare approach.

Future Prospects and Challenges

Declining Influence and Structural Weaknesses

Multiple factors indicate the CPI (Maoist) faces increasingly difficult circumstances. The dramatic reduction in affected districts, elimination of senior leadership, and improved security force capabilities suggest the movement’s territorial control is contracting rapidly. The death of experienced leaders like Basavaraju has created leadership gaps that may be difficult to fill with equally capable successors.

Ideological appeal appears to be waning, particularly among educated youth who historically formed an important recruitment base. Improved government development programs and better connectivity in tribal areas have reduced the organization’s ability to exploit grievances and maintain local support.

Persistent Challenges and Resilience Factors

Despite setbacks, several factors suggest the Maoist challenge may persist beyond the government’s 2026 deadline. The organization’s decentralized structure, deep forest hideouts, and remaining sympathizer networks provide resilience against security operations. Persistent issues of tribal land rights, displacement due to mining projects, and inadequate development may continue providing recruitment opportunities.

The CPI (Maoist) has demonstrated adaptive capacity throughout its history, surviving multiple leadership crises and security crackdowns. Their underground organizational structure and experience in clandestine operations suggest they may survive the current pressure and potentially resurge if conditions become favorable.

Government Strategy Assessment

The current government approach shows greater sophistication than previous purely security-focused strategies. The combination of targeted military operations, development spending, and infrastructure improvement addresses both immediate security threats and underlying socio-economic grievances.

However, success requires sustained commitment across multiple administrations and continued coordination between central and state governments. The March 2026 deadline, while providing focus and urgency, may be overly optimistic given the complex nature of the challenge and historical resilience of the movement.

Conclusion

The Communist Party of India (Maoist) represents a unique phenomenon in contemporary insurgency movements—a Marxist-Leninist organization that has sustained armed struggle for over five decades while adapting to changing political, social, and security environments. From its origins in the 1967 Naxalbari uprising to its current incarnation as India’s primary left-wing extremist group, the CPI (Maoist) has consistently challenged the Indian state’s authority in some of its most marginalized regions.

The organization’s sophisticated ideological framework, hierarchical structure, and strategic vision demonstrate the complexity of addressing insurgency rooted in genuine socio-economic grievances. While recent government efforts have significantly reduced Maoist territorial control and operational capacity, complete elimination remains a formidable challenge requiring sustained multi-dimensional engagement.

The conflict’s resolution ultimately depends not merely on security operations but on addressing the underlying issues of tribal rights, economic development, and social justice that provide legitimacy to the Maoist narrative. As India approaches the government’s self-imposed 2026 deadline, the success of counter-insurgency efforts will be measured not just by the absence of violence but by the integration of marginalized communities into the mainstream of Indian democracy and development.

The CPI (Maoist) phenomenon serves as a reminder that in diverse democracies like India, ensuring inclusive development and responsive governance remains essential for maintaining internal stability and national unity. The organization’s eventual fate will significantly influence India’s security landscape and provide important lessons for addressing ideologically motivated insurgencies in other contexts worldwide.