The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed in 1960, has long been celebrated as one of the most successful international water-sharing agreements in history. For over six decades, India and Pakistan have adhered to its terms—even during times of war and severe diplomatic breakdowns. However, recent developments, ongoing disputes, and evolving water needs have sparked India’s demand to revisit and amend the treaty. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Indus Waters Treaty, its history, disputes, strategic implications, and why India now seeks changes to the decades-old agreement.

The Origins of the Indus Waters Treaty

The IWT was brokered by the World Bank and signed on September 19, 1960, by India and Pakistan. At the time, both nations were primarily agrarian economies, heavily dependent on river waters for irrigation and sustenance.

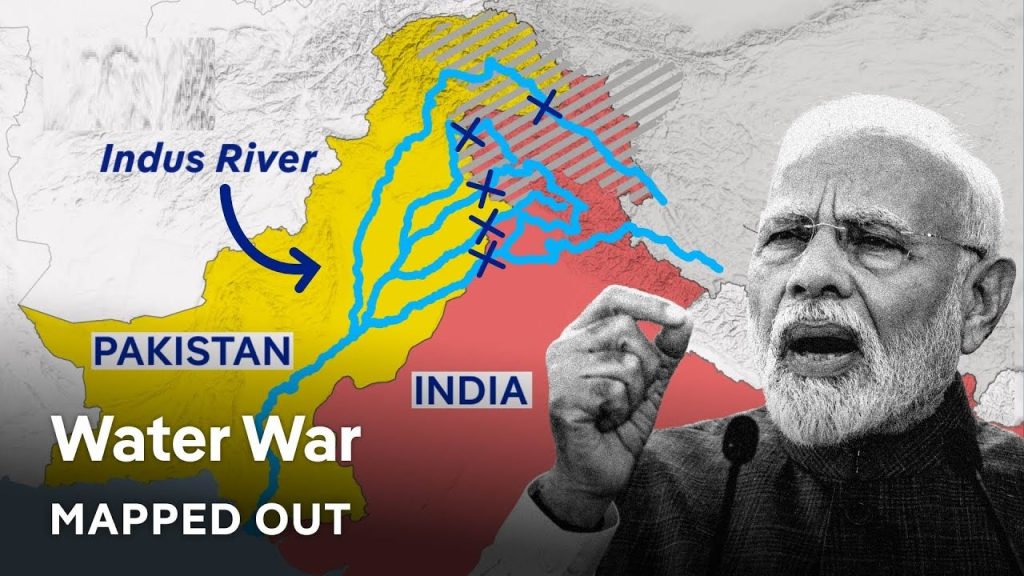

- Allocation of Rivers:

- Eastern Rivers (India’s control): Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej.

- Western Rivers (Pakistan’s control): Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab.

India was granted exclusive rights to use waters of the eastern rivers, while Pakistan retained rights over the western rivers. India, however, was permitted limited use of western rivers for irrigation, domestic needs, and run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects, without altering the flow significantly.

This arrangement ensured that both countries had access to dependable water resources while avoiding direct competition over the same river

Why the Treaty Was Significant

- Survived Wars and Conflicts: Despite wars in 1965, 1971, the Kargil conflict, and numerous terror attacks, the treaty has remained intact.

- World Bank’s Role: The World Bank acted as a facilitator, enabling infrastructure projects and dispute resolution mechanisms.

- Precedent in Water Diplomacy: Globally, the treaty is cited as a rare success story in transboundary river management.

How the Treaty Works in Practice

- India’s Rights: Full usage of eastern rivers and limited non-consumptive use of western rivers.

- Pakistan’s Rights: Almost 80% of the Indus basin waters (about 218 billion cubic meters annually).

- Resolution Mechanisms:

- Bilateral discussions between India and Pakistan.

- Referral to a neutral expert.

- Court of Arbitration (CoA) if disputes persist.

While effective on paper, this structure has often led to delays, litigation, and diplomatic standoffs.

The Current Dispute: Ratle Hydroelectric Project

One of the most contentious issues today revolves around the Ratle Hydroelectric Project:

- Location: Chenab River, Kishtwar district, Jammu & Kashmir.

- Capacity: 850 MW.

- India’s View: A run-of-the-river project, compliant with treaty provisions.

- Pakistan’s Concern: Even temporary storage for hydroelectric turbines could disrupt flows, giving India potential leverage to alter water supply.

Initially, Pakistan agreed to a neutral expert, but later demanded a Court of Arbitration, which India opposed due to its power to issue injunctions halting construction. The World Bank, frustrated by the stalemate, allowed both mechanisms to proceed simultaneously, deepening the deadlock.

Why India Wants Amendments to the Treaty

India’s primary concerns lie in Article IX, which governs dispute resolution. Current provisions allow Pakistan to escalate disputes prematurely, bypassing bilateral talks and causing prolonged project delays.

Key Reasons for India’s Push:

- Project Delays and Rising Costs: Almost every major project—Salal, Baglihar, Kishanganga, Ratle—has faced delays due to Pakistan’s objections.

- Asymmetric Water Allocation: India receives only about 20% of Indus basin waters despite being the upper riparian.

- Simultaneous Mechanisms: Allowing both neutral expert and Court of Arbitration processes undermines efficiency and creates diplomatic gridlock.

- Evolving Technology: Modern hydroelectric projects are run-of-the-river with minimal storage, unlike the massive reservoirs envisioned in the 1960s. The treaty needs to reflect these technological advancements.

- Strategic Leverage: India wants flexibility in case of escalating tensions with Pakistan, without being bound by outdated restrictions.

Pakistan’s Concerns and Objections

From Pakistan’s perspective, the treaty is a lifeline. The Indus system sustains its agriculture, which supports a majority of its population. Pakistan fears:

- Water Manipulation: India could potentially control water release, causing artificial droughts or floods.

- Diversion of Rivers: Projects like Kishanganga, which divert flows from one tributary to another, raise concerns about reduced availability for Pakistan’s own planned projects.

- Security Risks: In wartime, water scarcity could become an existential threat.

Strategic Implications of the Indus Waters Treaty

- India-China-Pakistan Triangle: Since the Indus and Sutlej originate in Tibet, China also plays a critical role as an upstream riparian. If India disregards treaty norms, China could retaliate on the Brahmaputra.

- Regional Stability: Water insecurity in Pakistan could escalate tensions, fueling anti-India sentiments.

- Domestic Politics: In India, calls to abrogate the treaty often arise after terror attacks (e.g., Uri, Pulwama). However, abrogation carries massive diplomatic and environmental risks.

Examples of Ongoing and Past Projects

- Kishanganga Project (330 MW): Disputed due to diversion of waters, but upheld by arbitration with modifications.

- Baglihar Project: Faced delays and objections but eventually approved by neutral experts.

- Salal Dam: One of the earliest projects slowed down due to Pakistani resistance.

- Ratle Project: Now the center of the latest dispute.

Can India Abrogate the Treaty?

While some voices call for scrapping the IWT, this is not practically feasible:

- International Backlash: Abrogation would damage India’s reputation as a responsible global power.

- Environmental Challenges: Redirecting massive Himalayan rivers is technically unfeasible and ecologically disastrous.

- China Factor: It would set a precedent for China to restrict Brahmaputra waters flowing into India.

Instead, amendments and renegotiations appear to be the more practical and strategic route.

Future of the Indus Waters Treaty

Likely Pathways Forward:

- Hierarchy in Dispute Resolution: India wants disputes to move step-by-step—bilateral talks first, neutral expert next, and Court of Arbitration as a last resort.

- Full Utilization of Eastern Rivers: India currently underutilizes some of its share; projects like Shahpur Kandi and Ujh are aimed at capturing the remaining waters.

- Sustainable Hydropower: Focus on run-of-the-river projects with minimal ecological disruption.

- Climate Change Adaptation: Both countries face increasing variability in river flows, demanding cooperation on flood management and drought preparedness.

Lessons from Global Water Disputes

Similar disputes worldwide show the delicate balance of transboundary rivers:

- Nile Basin: Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam has alarmed Egypt, which depends on the Nile.

- Mekong River: Southeast Asian nations face disputes over China’s upstream dams.

- Colorado River: U.S.-Mexico water-sharing challenges highlight the importance of cooperation.

The Indus Waters Treaty, despite its flaws, remains a global model. The challenge lies in modernizing it for contemporary realities without destabilizing the fragile India-Pakistan relationship.

Conclusion

The Indus Waters Treaty is not merely about rivers; it is about peace, security, and survival in South Asia. For over sixty years, it has withstood wars, political upheavals, and terrorism. Yet, the growing demands of populations, technological advancements, and persistent disputes make amendments inevitable.

India’s call to renegotiate the treaty is not about denying water to Pakistan but about updating an outdated framework to suit modern realities. Any new arrangement must balance India’s developmental needs with Pakistan’s existential concerns, while also considering the broader geopolitics of South Asia and China’s upstream influence.

In essence, the future of the Indus Waters Treaty will determine whether rivers remain a bridge of cooperation or a weapon of conflict between India and Pakistan.

Understanding the Indus Waters Treaty: Why India Seeks Amendments with Pakistan

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed in 1960, has long been celebrated as one of the most successful international water-sharing agreements in history. For over six decades, India and Pakistan have adhered to its terms—even during times of war and severe diplomatic breakdowns. However, recent developments, ongoing disputes, and evolving water needs have sparked India’s demand to revisit and amend the treaty. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Indus Waters Treaty, its history, disputes, strategic implications, and why India now seeks changes to the decades-old agreement.

The Origins of the Indus Waters Treaty

The IWT was brokered by the World Bank and signed on September 19, 1960, by India and Pakistan. At the time, both nations were primarily agrarian economies, heavily dependent on river waters for irrigation and sustenance.

- Allocation of Rivers:

- Eastern Rivers (India’s control): Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej.

- Western Rivers (Pakistan’s control): Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab.

India was granted exclusive rights to use waters of the eastern rivers, while Pakistan retained rights over the western rivers. India, however, was permitted limited use of western rivers for irrigation, domestic needs, and run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects, without altering the flow significantly.

This arrangement ensured that both countries had access to dependable water resources while avoiding direct competition over the same rivers.

Why the Treaty Was Significant

- Survived Wars and Conflicts: Despite wars in 1965, 1971, the Kargil conflict, and numerous terror attacks, the treaty has remained intact.

- World Bank’s Role: The World Bank acted as a facilitator, enabling infrastructure projects and dispute resolution mechanisms.

- Precedent in Water Diplomacy: Globally, the treaty is cited as a rare success story in transboundary river management.

How the Treaty Works in Practice

- India’s Rights: Full usage of eastern rivers and limited non-consumptive use of western rivers.

- Pakistan’s Rights: Almost 80% of the Indus basin waters (about 218 billion cubic meters annually).

- Resolution Mechanisms:

- Bilateral discussions between India and Pakistan.

- Referral to a neutral expert.

- Court of Arbitration (CoA) if disputes persist.

While effective on paper, this structure has often led to delays, litigation, and diplomatic standoffs.

The Current Dispute: Ratle Hydroelectric Project

One of the most contentious issues today revolves around the Ratle Hydroelectric Project:

- Location: Chenab River, Kishtwar district, Jammu & Kashmir.

- Capacity: 850 MW.

- India’s View: A run-of-the-river project, compliant with treaty provisions.

- Pakistan’s Concern: Even temporary storage for hydroelectric turbines could disrupt flows, giving India potential leverage to alter water supply.

Initially, Pakistan agreed to a neutral expert, but later demanded a Court of Arbitration, which India opposed due to its power to issue injunctions halting construction. The World Bank, frustrated by the stalemate, allowed both mechanisms to proceed simultaneously, deepening the deadlock.

Why India Wants Amendments to the Treaty

India’s primary concerns lie in Article IX, which governs dispute resolution. Current provisions allow Pakistan to escalate disputes prematurely, bypassing bilateral talks and causing prolonged project delays.

Key Reasons for India’s Push:

- Project Delays and Rising Costs: Almost every major project—Salal, Baglihar, Kishanganga, Ratle—has faced delays due to Pakistan’s objections.

- Asymmetric Water Allocation: India receives only about 20% of Indus basin waters despite being the upper riparian.

- Simultaneous Mechanisms: Allowing both neutral expert and Court of Arbitration processes undermines efficiency and creates diplomatic gridlock.

- Evolving Technology: Modern hydroelectric projects are run-of-the-river with minimal storage, unlike the massive reservoirs envisioned in the 1960s. The treaty needs to reflect these technological advancements.

- Strategic Leverage: India wants flexibility in case of escalating tensions with Pakistan, without being bound by outdated restrictions.

Pakistan’s Concerns and Objections

From Pakistan’s perspective, the treaty is a lifeline. The Indus system sustains its agriculture, which supports a majority of its population. Pakistan fears:

- Water Manipulation: India could potentially control water release, causing artificial droughts or floods.

- Diversion of Rivers: Projects like Kishanganga, which divert flows from one tributary to another, raise concerns about reduced availability for Pakistan’s own planned projects.

- Security Risks: In wartime, water scarcity could become an existential threat.

Strategic Implications of the Indus Waters Treaty

- India-China-Pakistan Triangle: Since the Indus and Sutlej originate in Tibet, China also plays a critical role as an upstream riparian. If India disregards treaty norms, China could retaliate on the Brahmaputra.

- Regional Stability: Water insecurity in Pakistan could escalate tensions, fueling anti-India sentiments.

- Domestic Politics: In India, calls to abrogate the treaty often arise after terror attacks (e.g., Uri, Pulwama). However, abrogation carries massive diplomatic and environmental risks.

Examples of Ongoing and Past Projects

- Kishanganga Project (330 MW): Disputed due to diversion of waters, but upheld by arbitration with modifications.

- Baglihar Project: Faced delays and objections but eventually approved by neutral experts.

- Salal Dam: One of the earliest projects slowed down due to Pakistani resistance.

- Ratle Project: Now the center of the latest dispute.

Can India Abrogate the Treaty?

While some voices call for scrapping the IWT, this is not practically feasible:

- International Backlash: Abrogation would damage India’s reputation as a responsible global power.

- Environmental Challenges: Redirecting massive Himalayan rivers is technically unfeasible and ecologically disastrous.

- China Factor: It would set a precedent for China to restrict Brahmaputra waters flowing into India.

Instead, amendments and renegotiations appear to be the more practical and strategic route.

Future of the Indus Waters Treaty

Likely Pathways Forward:

- Hierarchy in Dispute Resolution: India wants disputes to move step-by-step—bilateral talks first, neutral expert next, and Court of Arbitration as a last resort.

- Full Utilization of Eastern Rivers: India currently underutilizes some of its share; projects like Shahpur Kandi and Ujh are aimed at capturing the remaining waters.

- Sustainable Hydropower: Focus on run-of-the-river projects with minimal ecological disruption.

- Climate Change Adaptation: Both countries face increasing variability in river flows, demanding cooperation on flood management and drought preparedness.

Lessons from Global Water Disputes

Similar disputes worldwide show the delicate balance of transboundary rivers:

- Nile Basin: Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam has alarmed Egypt, which depends on the Nile.

- Mekong River: Southeast Asian nations face disputes over China’s upstream dams.

- Colorado River: U.S.-Mexico water-sharing challenges highlight the importance of cooperation.

The Indus Waters Treaty, despite its flaws, remains a global model. The challenge lies in modernizing it for contemporary realities without destabilizing the fragile India-Pakistan relationship.

Conclusion

The Indus Waters Treaty is not merely about rivers; it is about peace, security, and survival in South Asia. For over sixty years, it has withstood wars, political upheavals, and terrorism. Yet, the growing demands of populations, technological advancements, and persistent disputes make amendments inevitable.

India’s call to renegotiate the treaty is not about denying water to Pakistan but about updating an outdated framework to suit modern realities. Any new arrangement must balance India’s developmental needs with Pakistan’s existential concerns, while also considering the broader geopolitics of South Asia and China’s upstream influence.

In essence, the future of the Indus Waters Treaty will determine whether rivers remain a bridge of cooperation or a weapon of conflict between India and Pakistan.